, where E is the energy and p is the momentum. This is the equation for the kinetic energy.

, where E is the energy and p is the momentum. This is the equation for the kinetic energy.Science communicators often describe quantum systems as exploring every possible state. "The particle goes through both slits," or "travels every possible path." I first want to explore the how we formulate this idea.

Let's start with a one dimensional system. In classical physics, we make statements such as , where E is the energy and p is the momentum. This is the equation for the kinetic energy.

, where E is the energy and p is the momentum. This is the equation for the kinetic energy.

In quantum mechanics, though, we might not know the exact momentum. We might want to keep track of the properties of any number of possible states, so that we can explore all of them at once. How can we make this easier?

We can start by making up some notation for a state with a known momentum. We will let  denote a state with a known momentum 'p.'

denote a state with a known momentum 'p.'

We want to be able to add many of these states together so that we can work with all of them at once. To this effect, we will let momentum states be members of a vector space. There are infinitely many possible momenta, so this vector space is infinite-dimensional. Each of the infinitely many momentum states is like an orthogonal direction.

The magnitudes of these states has to do with probability. We're adding together many states because we're not sure which one we're in, and so the magnitudes allow us to encode which ones are more likely.

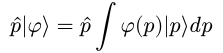

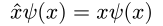

To do things with our system, we'll want to define operators that act on the states. These will be like infinite-dimensional matrices, acting on our infinite-dimensional vector space of states. For instance, we will define an operator  such that

such that  . This means our momentum states are eigenvectors of what we are going to call the momentum operator or momentum observable.

. This means our momentum states are eigenvectors of what we are going to call the momentum operator or momentum observable.

Now, we can, in a sense, simultaniously calculate the energies of all of our momentum states. For individual states, our classical equation becomes the following:

By linearity, even if our state is the sum of many momentum states, this formula will multiply each individual state by that state's kinetic energy.

So far, this is essentially just a weird way of writing the same calculation we had before. There's two benefits that I haven't mentioned yet, though.

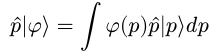

We can write collections of many states as, essentially, functions. If we have a distribution  , we can use it to define a state,

, we can use it to define a state,

Now we have a more interesting, powerful way of applying operators to whole distributions of states.

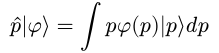

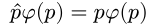

We can see, then, that applying the momentum operator to a state is the same as multiplying our distribution function by the momentum variable.

Through a little abuse of notation, we often say that

So far, we've only talked about momentum, but there's another fundamental quantity that we haven't touched on yet - position.

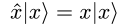

Everything that we've talked about so far can be applied to position as well. We can have a position operator, with position eigenstates, and write whole distributions of position states.

What we don't have yet, is a way of relating these position states, distributions, and operators, to the momentum states, distributions, and operators. This is where the canonical commutation relation comes in.

We have experimental evidence for the Heisenberg uncertainty principle - that knowing position precisely results in not knowing momentum precisely, and vice versa. The canonical commutation relation is a way of formalizing this.

... where I is the identity operator. In natural units we drop the planck's constant, so I will do this from now on.

Using basic calculus, it can be shown that  satisfies this relation in the position basis, when thought of as acting on the position distribution, and

satisfies this relation in the position basis, when thought of as acting on the position distribution, and satisfies this relation in the momentum basis, when thought of as acting on the momentum distribution.

satisfies this relation in the momentum basis, when thought of as acting on the momentum distribution.

So, how do we, you know, *do phyics*?

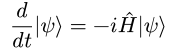

Well, the end goal is usually to find the "time evolution" of a state. That is, we want to know

This is where the Schrodinger equation comes in. An explanation of where this comes from is beyond the scope of this page, but there's a good Quantum Sense video about deriving it.

The H operator here is called the Hamiltonian, and it essentially corresponds to the total energy.

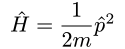

For example, for a totally free particle, or a particle in an infinite potential well, we have:

Whatever our Hamiltonian is, we can plug it in to the Schrodinger equation and get a differential equation to solve.